Assignment 1

Cultural Heritage By the Numbers

Part 1: Objects of Interest

Looking through the Harvard Art Museum website, I found a few objects of interest. I tried using the csv file to look through as well, but since it is not well sorted or formatted, it is harder to find objects of interest. There are also no visuals, so you are essentially only able to see objects by their description. The website was much easier to use, as there are visuals for each piece and ways of searching and sorting by categories, such as artist, culture, time period, etc. While it is true you can also search on the csv using CMD-F (I am using Mac OS). Therefore, I had a much easier time using the sorted website over the raw csv data, which in hindsight, seems pretty obvious. When searching for art pieces, the first thing I did was look for my two favorite artists: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Nam June Paik.

“Bird on Money” by Jean-Michel Basquiat

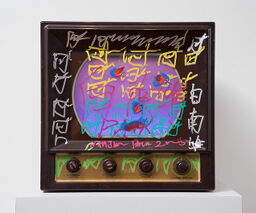

“TV Buddha” by Nam June Paik

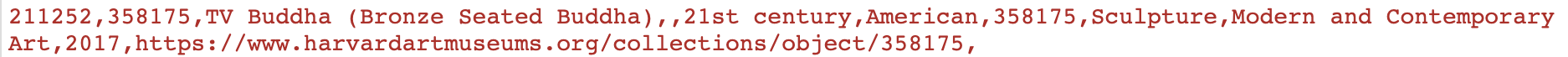

Unfortunately, while I was unable to find any of Basquiat’s pieces, I was able to find some of Paik’s. Two of his pieces that I found interesting were “TV Buddha”, shown above, and “White TV.”

“TV Buddha” is a really interesting piece for me. While I am not very good at explaining why I enjoy these pieces, or how they make me feel, I do really like how a lot of Paik’s pieces such as this one bring together the traditional and the modern. An ancient Buddha statue is staring at itself through a digital TV, being recorded by a camera.

“White TV” is another piece that I really love. It shows a TV whose face and sides have been covered with handwritten Korean-Chinese symbols called hanja, and has a face painted onto the screen. While I am unable to read hanja, you can see that he wrote his name in English below the screen, and the year he created it. Here, he is essentially using the TV as a canvas to paint whatever he likes on it because painting does not need to be constricted by mediums such as a blank canvas.

His pieces are a mash of the “East” and “West” cultures, the spiritual and the digital. I really love how Paik combines his Korean heritage with the American, making such a thought-provoking piece. As a half-Korean myself, his pieces really inspire me to make art that combines all of my heritages into one (Korean, Italian, and American) and to embrace the idea that “Eastern” and “Western” cultures don’t have to be so different. I don’t belong to one specific cultural identity and do not have to feel the need to adhere to one of those backgrounds’ ideals. I am who I want to be.

I did not want to pick three of Paik’s pieces because I wanted an opportunity to look around the website more. Interestingly enough, when looking at the metadata of these two pieces on the csv file, I found that both of these pieces are categorized under American culture.

I found this interesting because Nam June Paik is Korean-American. He was born in Korea but moved to the US as an adult. I assumed his pieces would be labeled Korean because of his ethnicity, but now thinking about it, it does make sense that these would be labeled as American. Paik made these pieces while he was living in the US, not in Korea. Was he an American citizen when these pieces were created? That I do not know. However, based on these findings, I can see that the database does not support multiethnic tags for culture, and only one must be chosen.

After seeing that Paik’s work was considered American, I was curious to see if there were art pieces listed as Korean at the Harvard Art Museum. There were a little less than 1,500 entries that I had found, most of them being artifacts from old Korean dynasties. I wanted to find paintings, so I looked for them and found a piece that interested me: “Branch of Fruiting Pomegranate” by Rae-Hyeon Park.

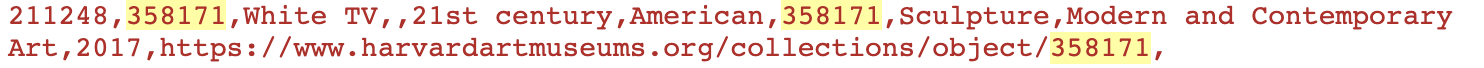

“Branch of Fruiting Pomegranate” by Rae-Hyeon Park

This piece depicts two pomegranate fruits hanging off of a tree branch, drawn in a traditional “Eastern” style. This piece intrigued me because as far as I know, pomegranates do not grow in Korea. After doing some research, I found out this was true, and that her pieces are centered around creating “Eastern” style pieces using “Western” objects. I found this to be a very interesting piece overall. However, I was unable to find the piece in the csv file and I could not figure out why.

Part 2: Items of a Specific Culture

For the next part, I decided to see the most and least-viewed objects of the Korean culture, since I believed it would be interesting to see and believed it would be a culture probably no one else in our class would choose. I first started with the most viewed:

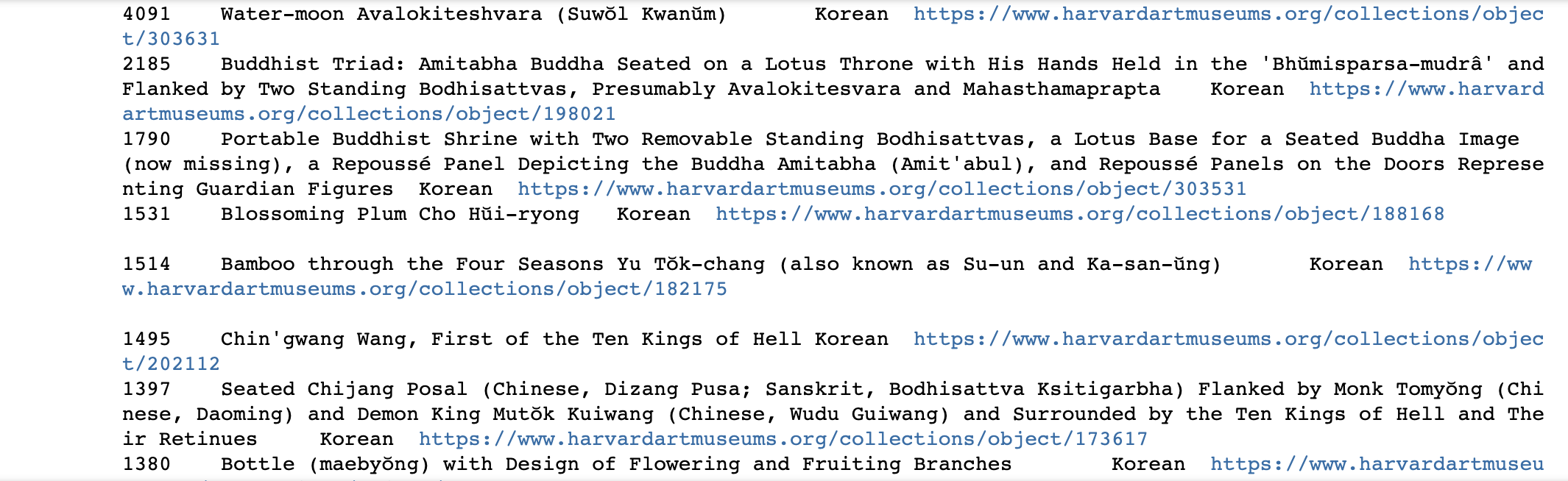

I found that all of the pieces, from what I could see, were either Buddhist sculptures or paintings or ink-washed-style paintings from the Jeoson or Koryo dynasties.

“Water-moon Avalokiteshvara” by Unknown Artist

“Blossoming Plum” by Hui-Ryong Jo

This makes sense because from what I saw, most of the Korean pieces on the website are from those eras of Korea, and there is not much in the realm of contemporary art. If there were contemporary pieces, they were still heavily influenced by traditional ink-washed pieces, such as the case of Rae-Hyeon Park’s aforementioned piece, which was created in 1959. Also, I believe that when people are looking for East Asian art pieces, they look for these styles of paintings or Buddhist sculptures, because they are the most well-known art pieces to come from there. Next, I took a look at the least viewed Korean art pieces:

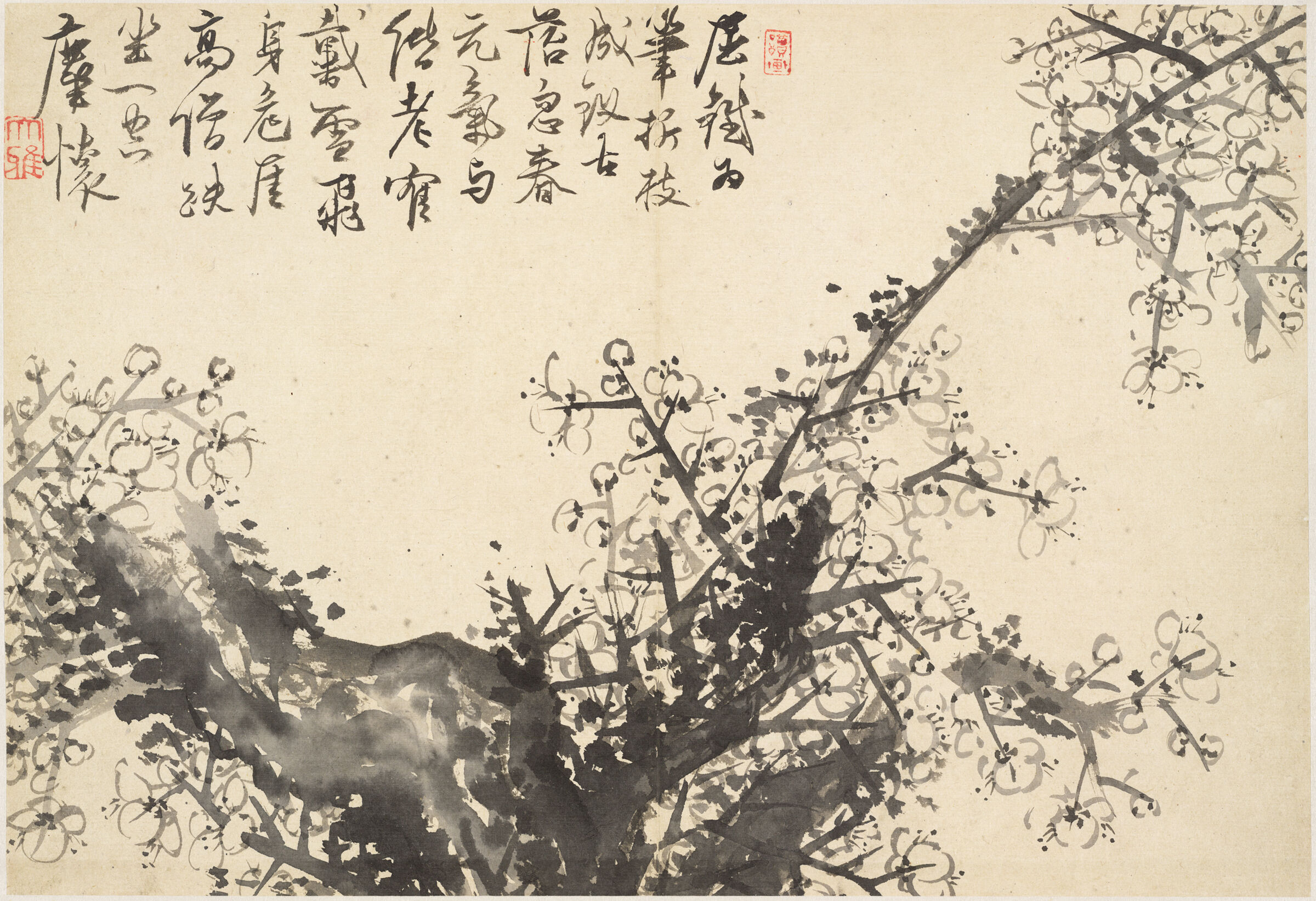

All of the pieces that I saw were sherds of Koryo-era ceramics and very small ones at that. I originally thought “sherd” was a typo of “shard,” but I found out sherds are actually fragments of broken ceramics, usually found at archeological sites.

“Sherd: Fragment of a Vessel, Probably from a Large Jar or Garden Stool”, Koryo Era

Every single piece that was listed had zero page views. This did not surprise me much either, as I had mentioned before that when looking through the website sorting by Korean culture, a large majority of the pieces shown were ceramics. Fragments may seem a lot less interesting to a viewer than a whole or mostly whole ceramic piece since a person is not really able to envision what the piece originally looked like based on a small sherd.

In conclusion, I was not totally surprised by these findings, and they fell under my expectations of what I generally expected to be popular and unpopular. It was unfortunate to see very few abstract pieces, in general and popularity, but expected, as abstract art is not for everyone.

Part 3: Comparing Three Cultures

For this part, I decided to be uncreative and choose the three largest parts of my own mixed cultural heritage to compare: American, Korean, and Italian. I hope this will be an interesting range of comparison, as I am choosing different cultures from different continents. However, I do know that Italy and America have somewhat close ties due to the large amount of Italian immigrants that have come to America (like my ancestors!). I believe that America will have by far the largest amount of pieces, due to this being an American museum, and that Korea will have the least, and Italian somewhere in the middle.

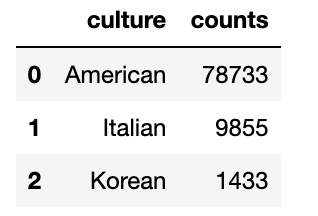

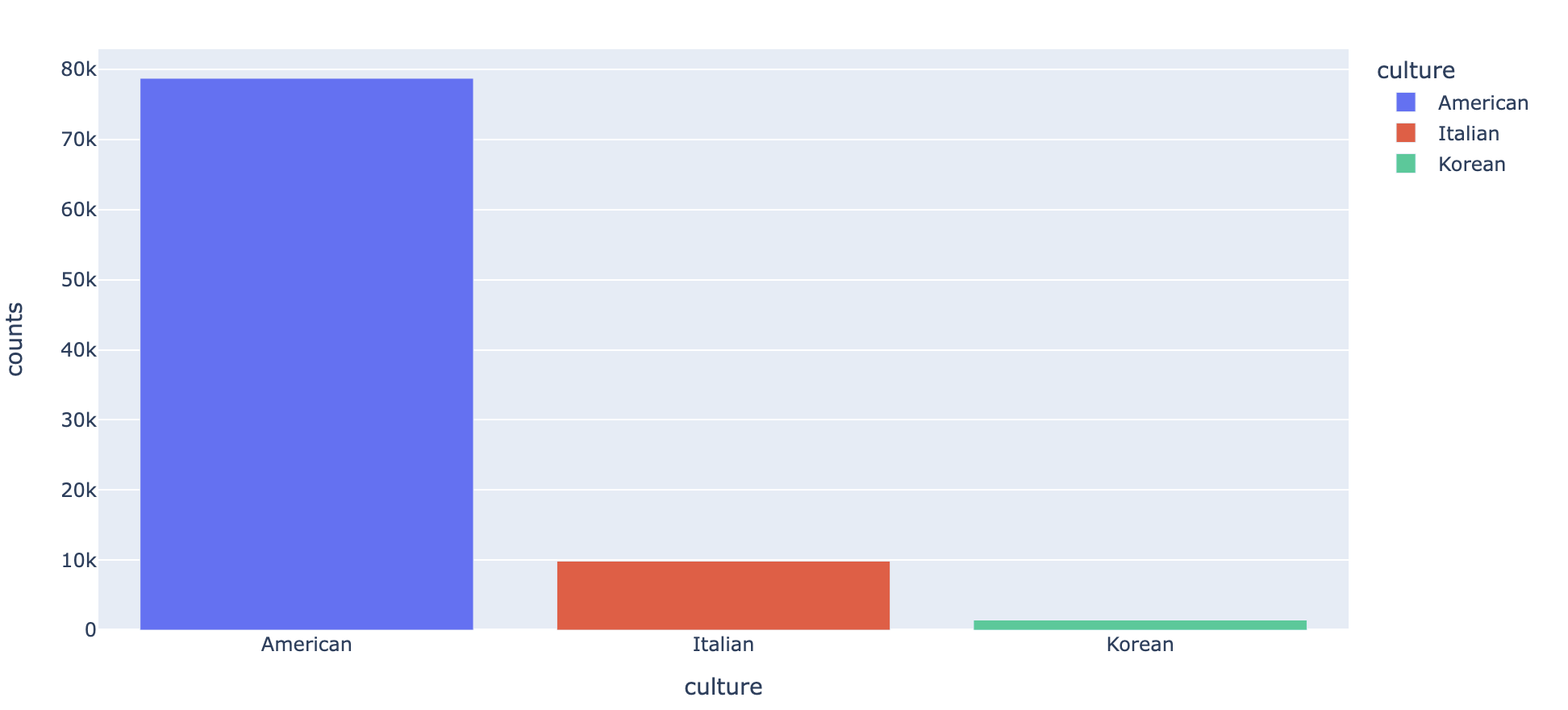

Unsurprisingly, American pieces are the largest majority compared to Italian and Korean, numbering at almost 80,000. Next is to create the accession year timeline, which looked like this:

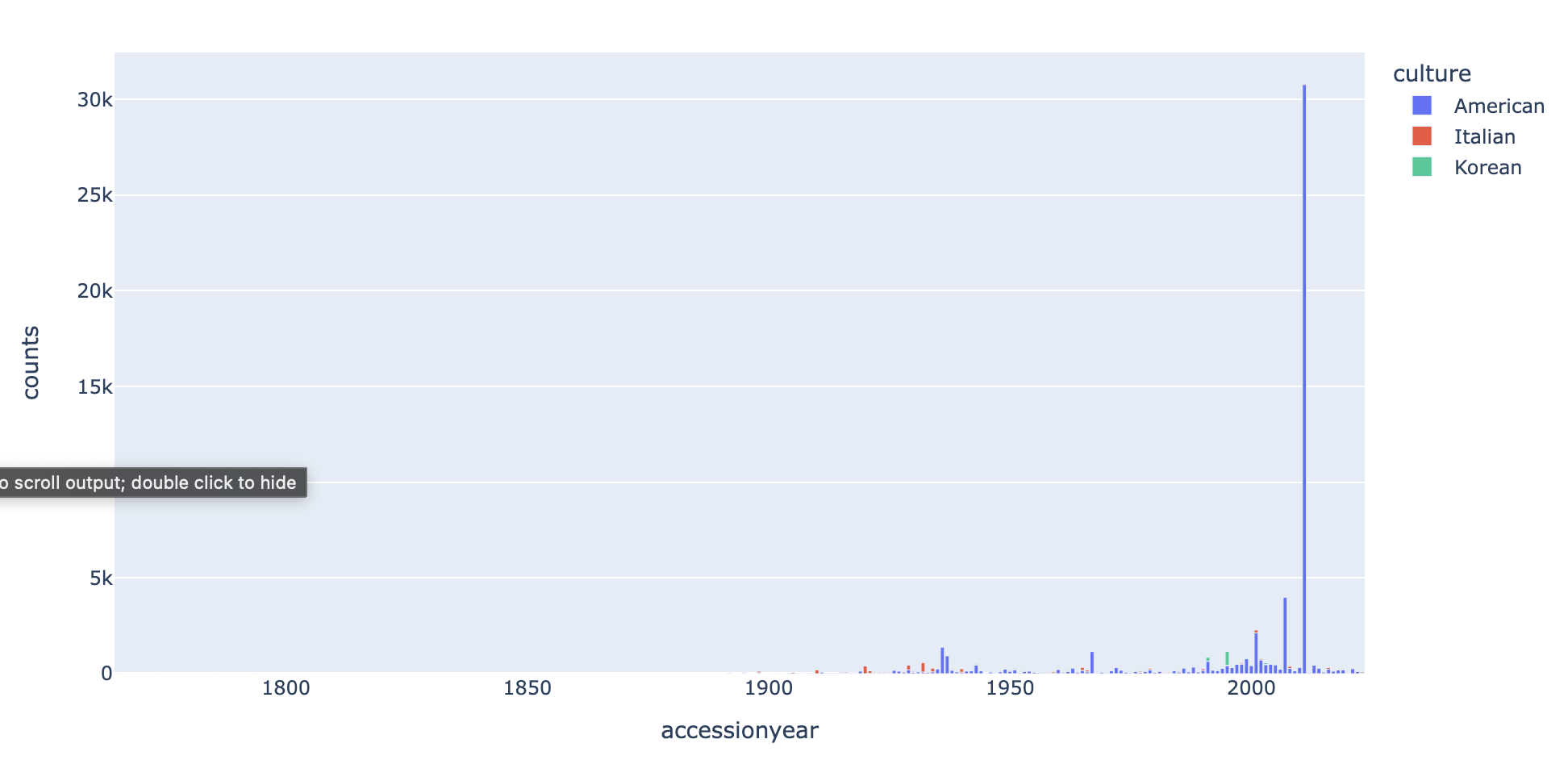

Looking at the graph here, I realized I probably messed up in picking American as one of my cultures. Since the sheer number of American pieces is so much larger than that of Korean, Italian, or any culture, it is really difficult to gauge the data properly. You can see that about 30,000 of the American pieces were all acquired in one year, 2011. Thankfully, you are able to zoom into the graph:

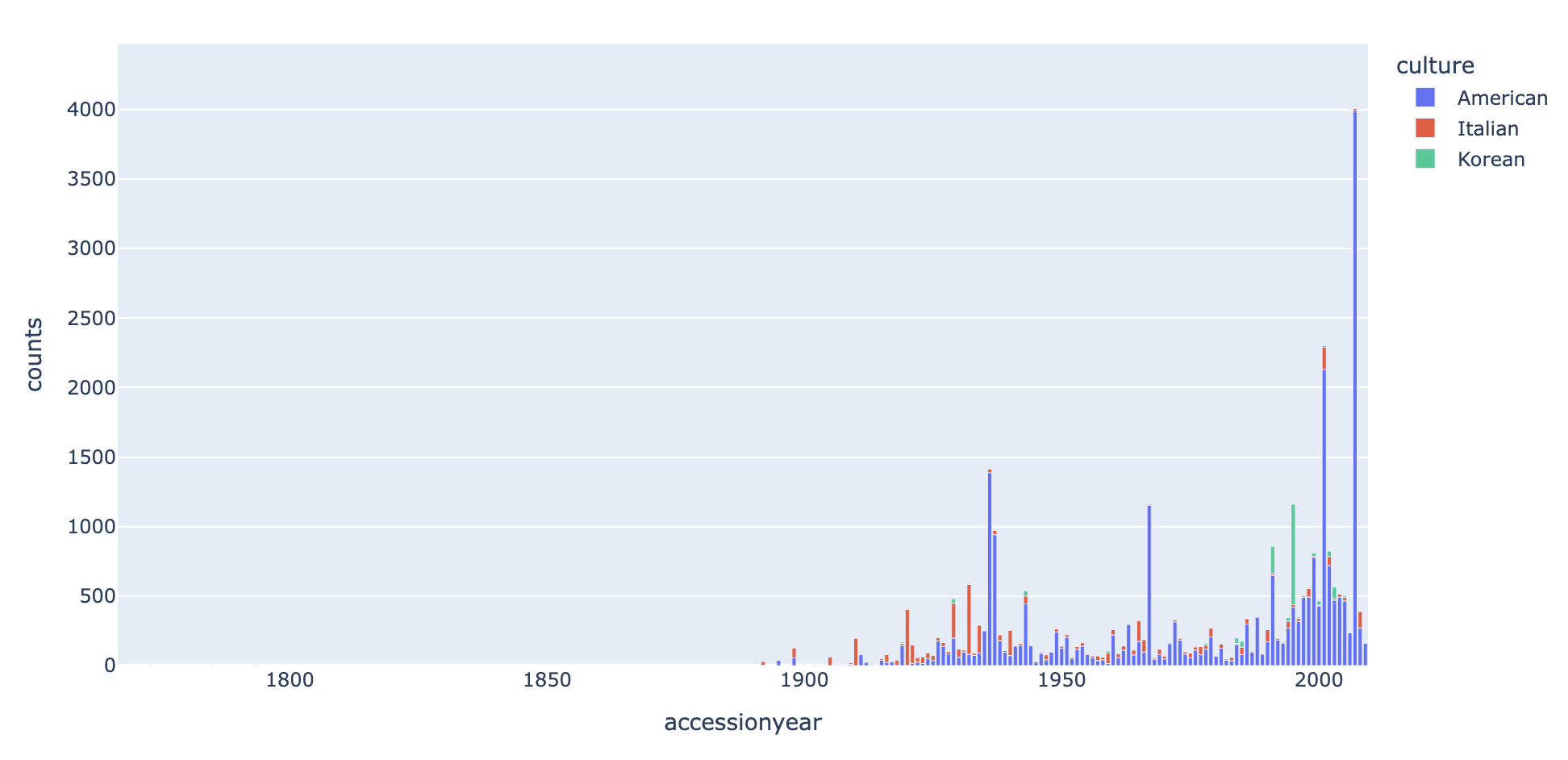

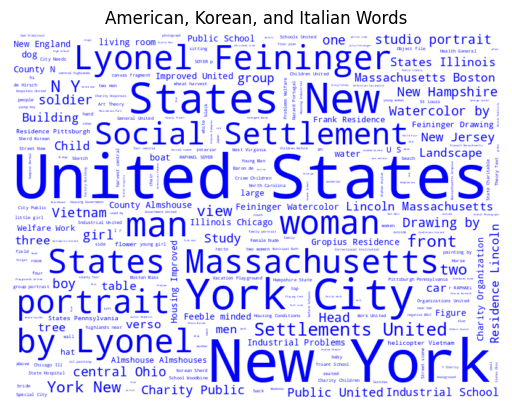

It is now a bit easier to tabulate data from this graph. While half of the graph does look blank, it is actually not. There were a few American acquisitions made as far back as 1795, but since it was only one or two pieces, they don’t appear compared to the almost 4,000 pieces acquired in 2007. One other interesting thing to note is that about half of the Korean pieces were all acquired in 1995. As for the Italian pieces, it looks as if a large majority of them were acquired between 1900 and 1940. During this time, especially between 1880 and 1930, there was a large influx of Italians immigrating to the United States, and it is possible that some wealthier immigrants came to donate pieces they had to the Harvard Art Museum. As for the large influx of Korean art in the 1990s, I am unsure and assume that a few people donated a large amount of Korean artifacts and paintings to the museum. From what I know, most Koreans immigrated to the United States between 1950 and 1980, due to the Korean War and subsequent brutal dictatorial leaders running the country such as Chung-Hee Park. I am unsure if these stretches of time are related to trends towards popularity in other cultures’ arts such as Italian or Korean, and as such cannot speak on the matter. While I have been to several museums in the US, considering that I live near New York City, I am unsure if these museums have followed similar trends that are shown here at the Harvard Art Museum. Obviously, there is a large amount of American art in the places I’ve visited, but as for Korean and Italian, from what I can remember, I have not even seen any Korean pieces, and some Italian pieces, but not as much as you see American. Italian is a sort of special case where most of what is seen from Italy is Roman, but there is also definitely a large amount of Renaissance art and possibly some more niche art pieces from movements such as Futurism. Moving on to the last part, we have the combined word cloud from these three cultures:

Unfortunately, I run into a similar problem to the previous accession graph where there are simply so many more American words they outweigh the other two cultures. I tried to see if I could color code the different cultures into one graph to see if any were truly not American, but I was unable to. Instead, I made a graph that does not have the American list in it:

Here, it is more obvious that there is a combination of the two cultures. It is very obvious here that the large majority of the Korean pieces are, again, sherds, and that most of the Italian pieces are religious art, having mostly words like “Madonna,” “Saint,” “Virgin,” and “Child”. I also saw that “Two” was a very frequent word but was unsure why. Obviously, based on the first graph, there is an overwhelming majority of American pieces at the Harvard Art Museum. This makes sense since it is an American museum. Most pieces in most American museums will be American, unsurprisingly. Some interesting things I also noticed is how often New York and Massachusetts appear. This makes sense as well because Harvard is located on the East Coast of the US, in Massachusetts. It would make sense that there is a large amount of art from Massachusetts because of this. As for New York, it has always been a cultural center and the largest city in the US, so it would make sense that there is also a large amount of art from Massachusetts’ close neighbor. The other thing I noticed was that there was a very large name: Lyonel Feininger. After doing some research, I found out that he was a German-American artist and one of the leading artists of Expressionism. He was also born in New York City, which would explain the large New York words that are all over the word cloud. A large amount of his works must have been donated to the Harvard Art Museum, because after searching his name, I found almost 24,000 results, meaning more than a quarter of the American pieces at the museum. I suspect that the large spike of American pieces on the previous graph in 2011 was because of his pieces being donated. Also, I should mention that these graphs were both generated with stopwords, mostly prepositions and “nan” and “untitled”. When the stopwords are absent, the largest words are nan and untitled in both word clouds shown. These word clouds were very interesting in better understanding what the largest amount of types of pieces of each culture are at the Harvard Art Museum.