Assignment 2

Working With A Corpus

For my data analysis, I want to compare different translations of the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf. My goal is to compare word frequencies between the books. When translating works, people will always translate words and phrases slightly differently, similar to how all people speak and write in their own unique prose. I want to measure the extent of the differences in these translations and see if that could mean certain words by certain translators would appear more frequently than those written by another translator. I have found three different versions of the book, two of which are written in the traditional poem style, and the third being heavily modified, being written in novel form. I have also a fourth copy of Beowulf written in the original Old English because I thought it would be interesting to analyze. I wanted to see if possibly the most frequently appearing words in the original version are close to the words written in Modern English when translated.

Part 1: Choosing the Works

At first, I had a hard time trying to figure out what I wanted to analyze, or even what book to take. A large amount of the books I read were newer books, ones that would not appear in a place like Project Gutenberg. One that came to mind was a book series I read as a child that I adored called Redwall, which takes place in a medieval-esque fantasy world where Anthropomorphic animals like mice, ferrets, and cats would go on adventures with some sort of goal in mind, usually slaying an antagonist such as a cat. The first of these books was written in 1986, which was evidently too recent to be in the Project Gutenberg database. After much thinking, I remembered the epic poem Beowulf. My father, an avid book reader, had this novel on a bookshelf in our home. The book had a man whose entire face was covered in chainmail, and inside was both English and some strange language inside the book with letters I had never seen before.

The Beowulf novel that’s in my house.

My dad eventually told me that the book had the original Old English translation of the translated page on the right side of each page, and I found that to be really intriguing. Being the voracious reader I was back in the day, I tried to read it, but this proved futile. The Modern English translation is still written in an archaic way, and it being in a poem form made it even more confusing for me to understand. I eventually gave up trying to read it, and unfortunately, I never actually tried to read it again at a later point in time since I stopped reading as much as I got into middle and high school. It seems that my love for languages has brought me back here, however, and I am excited to do this data analysis.

While looking through Project Gutenberg, I found a few translations and an Old English one. Two were written in the original poem-style, translated by John Lesslie Hall (1897) and Francis Barton Gummere (1910). The third took a bit more liberties and converted the poem into a modern-style novel, translated by Ernest J. B. Kirtlan (1914). I think it will be very interesting to compare these translations and see how much different the prose between the three different translations are, and I suspect the novel version will give the most differing results, as it is written with a less archaic and more modern prose. The Old English version is more for fun, it will obviously be very different from the translations, but I hope to be able to garner at least some interesting data from it, and be able to find an actual Old English translator online.

I tried to do some research into the authors, and I managed to find a little bit of information on both Hall and Gummere but nothing on Kirtlan. Hall (1856-1928) was an American professor of English at the College of William and Mary, in Williamsburg, Virginia, and seems to only be known for his translation of Beowulf. Gummere (1855-1919) was an American Quaker and an English and ancient language scholar who taught at Haverford College, in Haverford, Pennsylvania, a university that was founded by his grandfather. Along with Beowulf, he has translated a few other Old English works into modern English. His translation is also quoted to “remain the most successful attempt to render in modern English something similar to the alliterative pattern of the original” by literary scholar John Espey.

A picture of Francis Gummere.

Even looking simply at the first sentence of each novel, you can clearly see there is a difference in the prose between the three translators:

“Lo! the Spear-Danes’ glory through splendid achievements

The folk-kings’ former fame we have heard of,

How princes displayed then their prowess-in-battle.” (Hall)

“Lo, praise of the prowess of people-kings

of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped,

we have heard, and what honor the athelings won!” (Gummere)

“Now we have heard, by inquiry, of the glory of the kings of the people, they of the Spear-Danes, how the Athelings were doing deeds of courage.” (Kirtlan)

“Hwæt! wē Gār-Dena in geār-dagum

þēod-cyninga þrym gefrūnon,

hū þā æðelingas ellen fremedon.” (Original for reference)

Seeing this made me confident that I would be able to see actual results in my analysis, seeing that the translation prose actually seems pretty different from one another.

One thing I also found helpful in the Hall translation is that there is context given so that the terms used in the book, such as the Spear-Danes are explained. Some parts of the poem are also explained in clearer words in case the reader has trouble understanding what is happening (like me). This is also detrimental, however, since these words will also be included in the analysis, which might mildly skew the data.

Part 2: Analyzing the Corpus

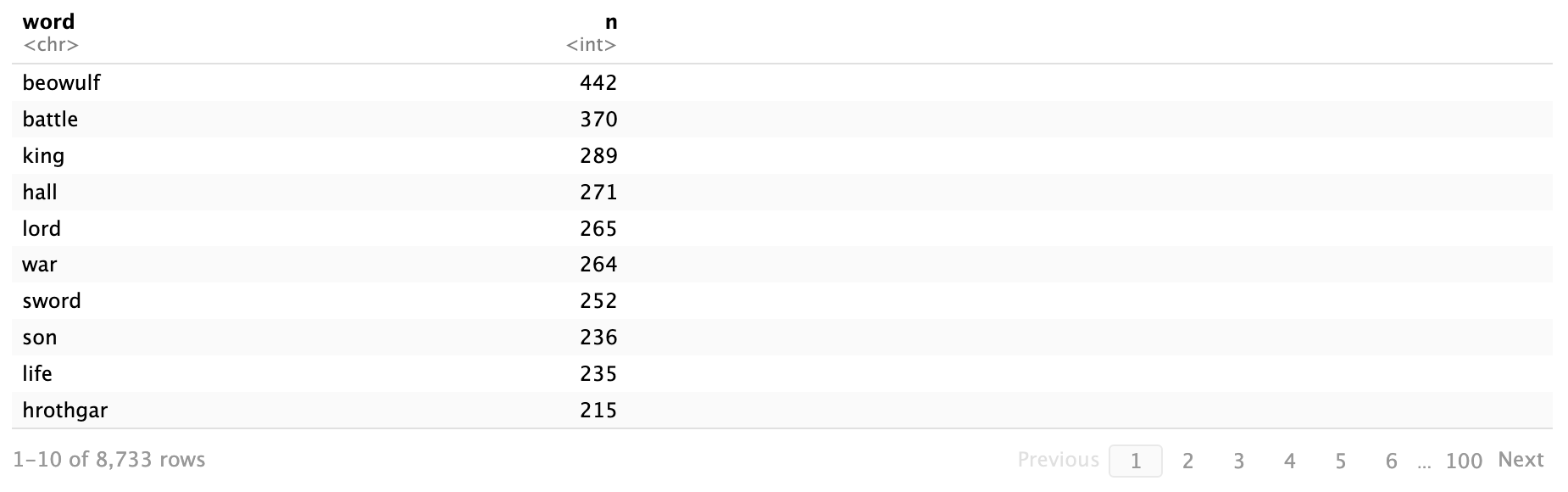

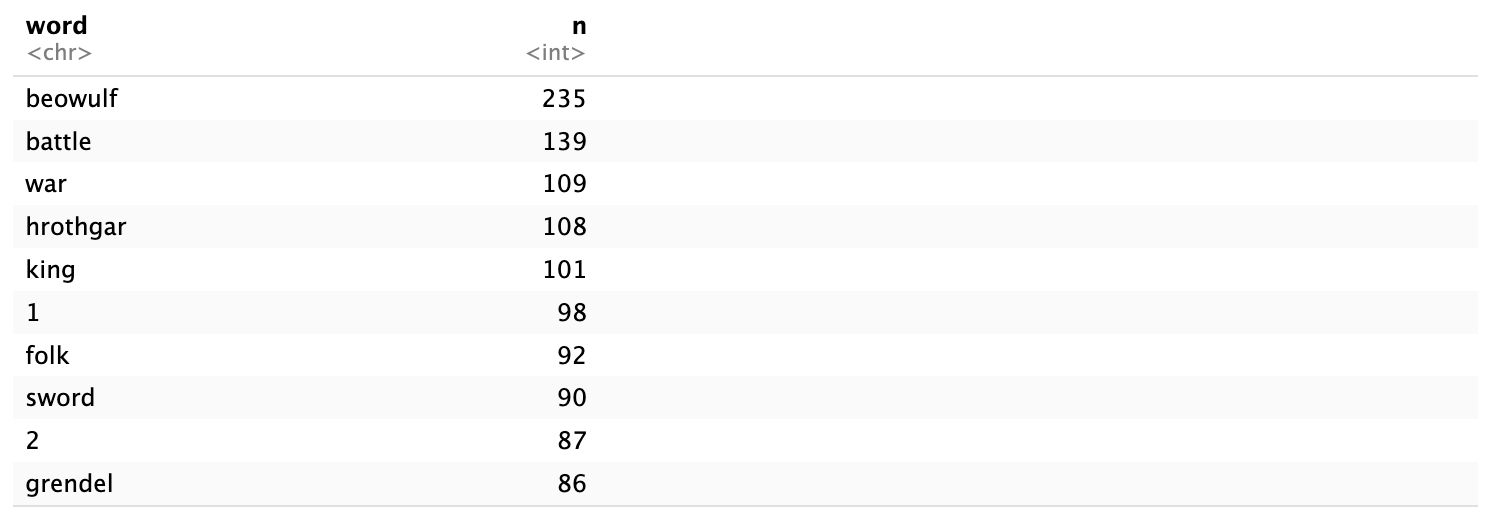

To start, I combined the three texts (excluding the original) into a corpus and measured the frequency of the three in R. These are the ten most frequent words between the three translations in a table:

Unsurprisingly, the most frequent and tenth most frequent words are both important characters often mentioned in the epic, the eponymous Beowulf and the Danish King Hrothgar. The other words include things like “king”, “battle”, “sword”, and “son”. This tells me that these words are ones that are probably the only single translation for specific words in Beowulf. You can see that all these words are nouns, which makes sense to me since they seem like the most obvious types of words to have only a single translation across multiple iterations of translations. Other words, like a verb, could have multiple meanings and can be translated in different ways depending on how a translator wishes to word something.

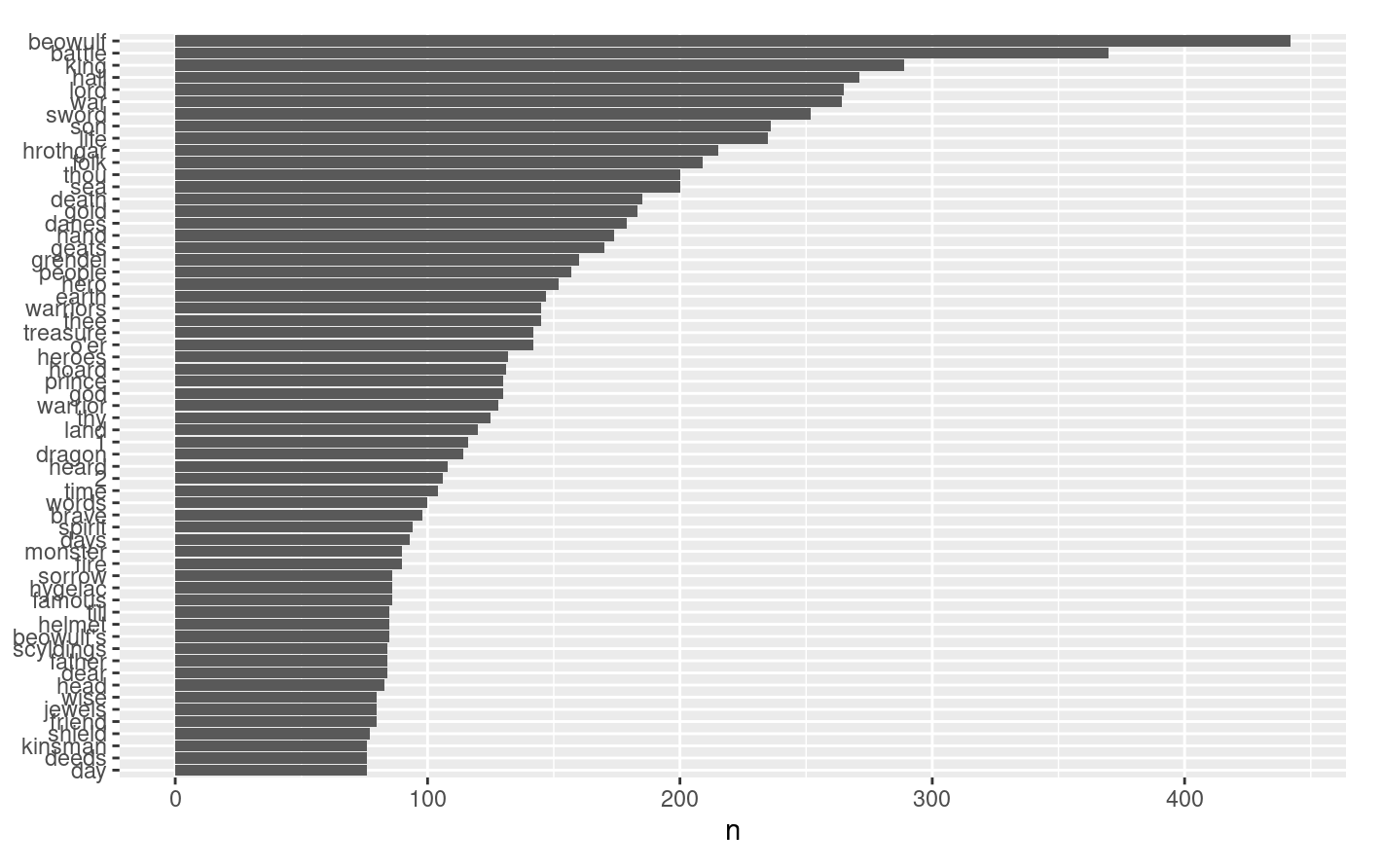

Next, I made a graph showing each word that appears more than 75 times. I wanted to see of most, if not all, of those words would also be nouns or proper nouns:

While a little hard to read, it seems that my theory is correct. All of the words are either nouns, proper nouns, pronouns, or prepositions. Seeing the pronouns and prepositions there also makes sense to me, as there is only one way to translate these words as well. Since English is not a gendered language, there should be only one type of each pronoun (except for he/she), noun, and preposition, and therefore only one translation. I also noticed that the number 1 and 2 appear on the graph, I am not really sure why they appear so frequently, but I assume it is most likely a mistake.

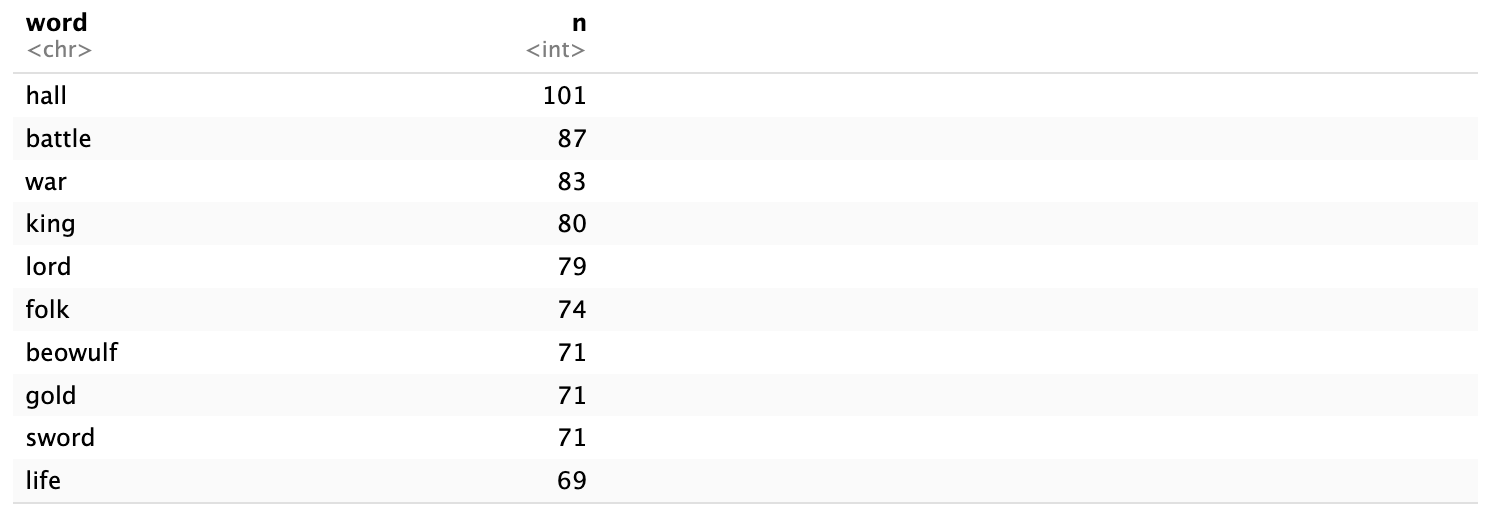

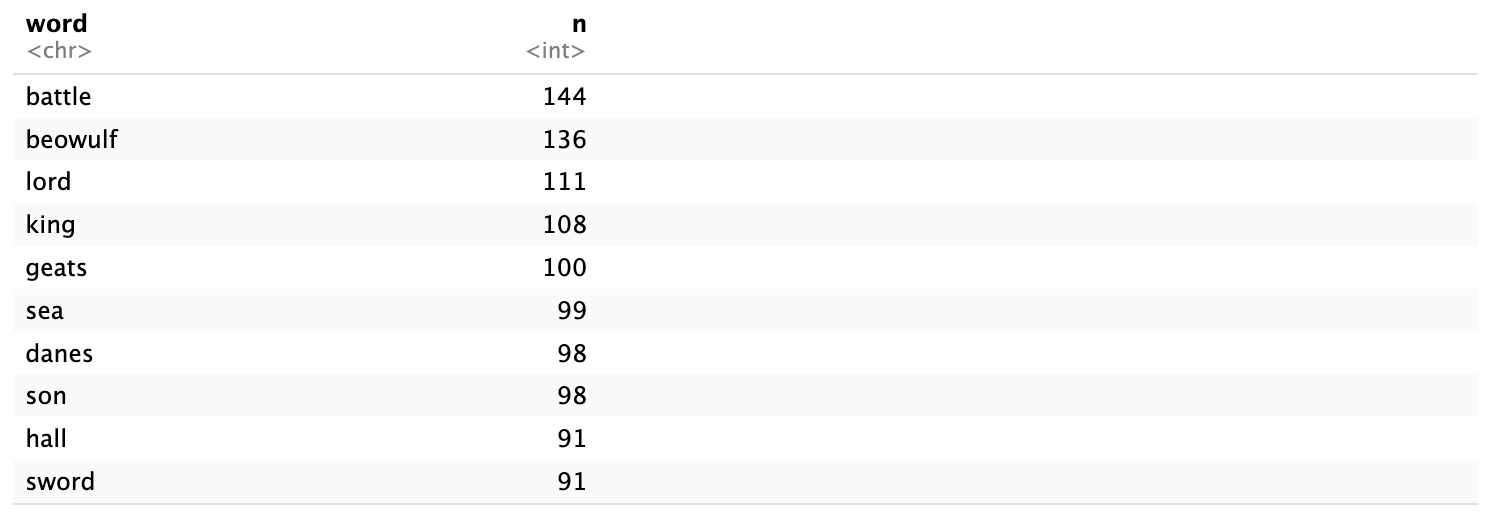

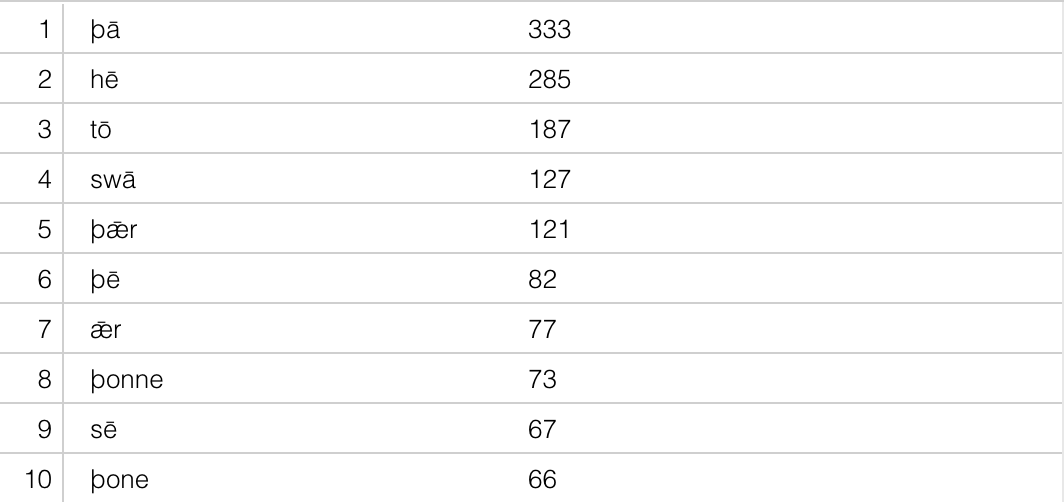

Next, I wanted to see the most frequently used words of each translation on their own, and I thought I could throw in the original epic as well for this:

Hall

Gummere

Kirtlan

Original

One thing I noticed right away is the sheer discrepancy in the frequency of the main character, Beowulf. I would expect them to be the same exact number, close to the Old English frequency of 40. However, all three translations have much more than 40 occurrences, with the lowest amount being from the Gummere translation, at 71. I believe that this is happening because of the sheer amount of extra notes and references in all three translations, bumping up the number significantly. You can see that in all three translations, the words battle, king, and sword are among the top ten most frequent words and that there are some words that only appear in one or two translations like the word war only appearing in the Hall and Gummere translations. There is still much discrepancy between the frequency of these words, which I tentatively believe means that there is in fact a difference between the prose of the three translators, as long as the extra notes are not skewing the data too much. I was also confused by the word geats in the Kirtlan translation, but it turns out that it is another word for Goths, an old Germanic tribe.

I had to to the original in Voyant Tools so I could add a list of Old English stopwords that I found. However, I think it still missed some, because the words I translated were things like pronouns, prepositions, and case identifiers that I assume the stopwords should catch. But I know next to nothing about Old English, so it’s possible that these were omitted from the stoplist for good reason. The protagonist, “Bēowulf” is the 24th most frequent word, which tells me there is probably a problem with my stopword list. However, this was the only one I was able to find, and I certainly do not have enough knowledge of Old English to try to make a list of my own, so this is the best I can do.

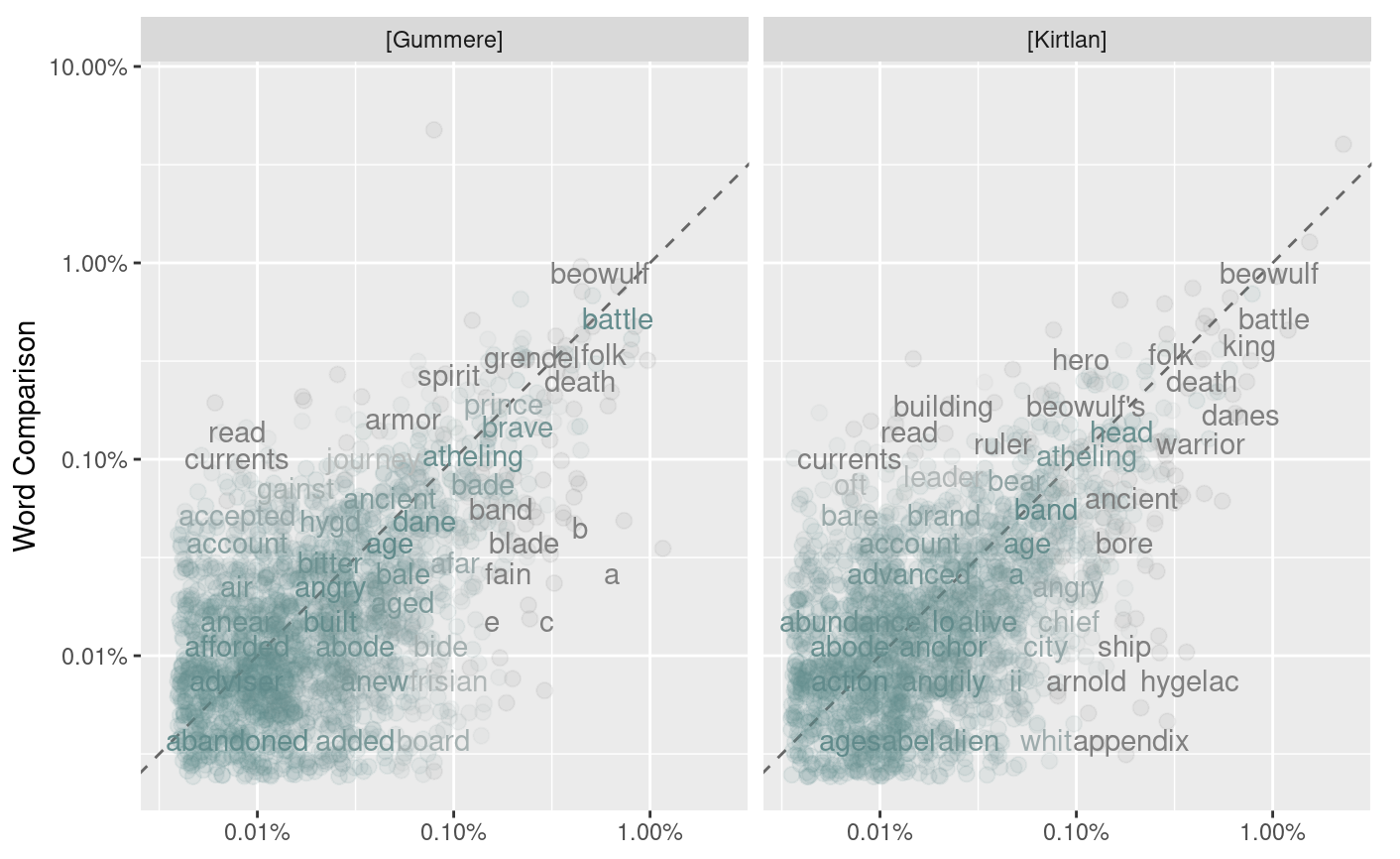

Next, I wanted to do the word comparison to see if certain words appear more often in one translation than another, I wanted to compare all three translations, but I was having some trouble with the R code and was therefore only able to compare the Hall translation to Gummere and Kirtlan, and not the Gummere and Kirtlan side by side.

Honestly, I found it difficult to read this data. It seems that there are only a few words that appear much more often in translation over the other, such as words like current, building, armor, and read appearing much more in the Hall translation over the Gummere and Kirtlan ones. Words like band, blade, and fain, as well as the letters a through e seem to appear more commonly in the Gummere translation. The letters are most likely more references in the book. Words such as ancient, bore, and hygelac (the king of the geats in Beowulf) appear more frequently in the Kirtlan translation. This graph was probably the best in telling me the more apparent difference in the usage of vocabulary between the three translations.

Conclusion

Looking back at my work, I believe that it might have been better to simply read the three translations to better understand the differences in prose between the three translations. There is too much bad data skewing the graphs from all the extra references and notes, making it much more difficult to analyze. Also, the choices in wording sentences are a very important factor in analyzing prose, something that cannot be analyzed by simply tabulating words. Overall though, I still think this was a good experience to have, showing me that not all things can be done simply by measuring word frequencies. Another issue I realized in my experiment is that since I don’t actually know Old English, I don’t exactly know if perhaps one translation could be considered “more accurate” than another. The prose could be affected by more than just the translator’s writing style, but also how much liberties they are taking in translating the work, by trying to stay more or less “true” to the original writing. Obviously, in the Kirtlan translation, the most liberties are taken in trying to translate the epic, but I cannot know the extent of the liberties taken between the Hall and Gummere translations. I also realize now that when the translation was written could also be a factor in how prose is written, but the translations I had were written within about a 30-year time span, so I believe that this means my data is not too different from one another. To conclude my project, I will say that my data could point to some evidence that there are some differences between the writing styles of these three different translators, but I could probably get more concrete evidence by analyzing the full sentences side-by-side.